Professor Carrasco’s 2017 NEH Fellowship Activities

Professor Michael Carrasco has returned to teaching after a year-long leave on a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. During this time he worked on his book From the Stone Painter’s Brush. In addition to this research he presented four papers with Dr. Joshua Englehardt that stem from their collaborative work on Olmec art and early writing in Mesoamerica. In addition, Carrasco also published two papers: “Nuevas Trazas de La Cultura Visual Olmeca: Las Potencialidades de la Aplicación de Técnicas Digitales de Visualización en la Arqueología” (with Englehardt and Mary Pohl) and “Representación y realidad: El objeto arqueológico en la era de reproducibilidad digital.”

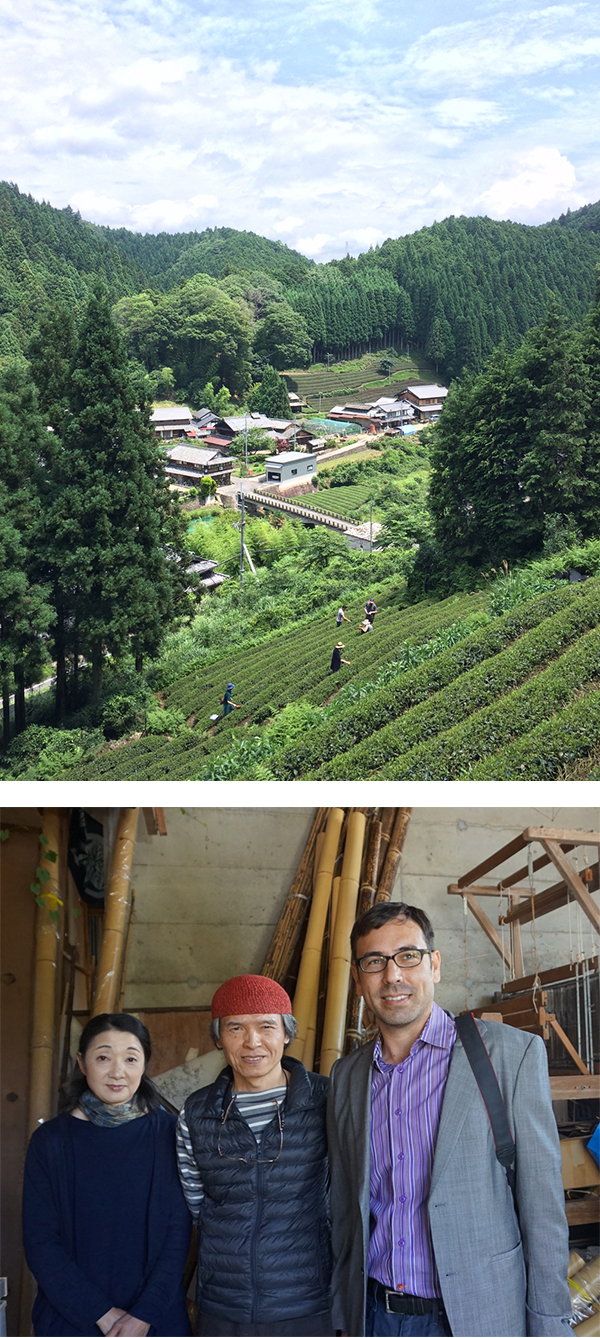

While in Japan in the summer, Prof. Carrasco spent two weeks in Wazuka, Kyoto Prefecture, studying tea cultivation and production with Obubu Tea in preparation for a course on art and food, and to better understand how the town is using the tea industry to develop heritage and experience tourism, both topics of considerable interest to cultural heritage studies. [See Carrasco’s participation and discussion of the Japanese Tea Master Course in the video below.]

While in Japan in the summer, Prof. Carrasco spent two weeks in Wazuka, Kyoto Prefecture, studying tea cultivation and production with Obubu Tea in preparation for a course on art and food, and to better understand how the town is using the tea industry to develop heritage and experience tourism, both topics of considerable interest to cultural heritage studies. [See Carrasco’s participation and discussion of the Japanese Tea Master Course in the video below.]

In October Carrasco returned to Oita Prefecture, Japan for five days on the Furusato Vision Project to interview bamboo artists and meet forestry experts. The Furusato Vision Project is sponsored by Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) and is designed to bring those who had taught on the JET program back to their Japanese “hometowns” or furusato. Carrasco will use this opportunity to further his research on the interrelationship between craft and gallery art (From mingei to obuje) with the goal of eventually curating an exhibition on the subject. For his work on bamboo art he was named an official Mejiron Foreign Correspondent to represent Oita Prefecture.

During his time in Oita Carrasco met bamboo artists Takami Yasuhiro, Otani Kenichi, Morigami Jin, and Shimizu Takayuki; visited the Oita Prefecture Bamboo Craft Training Center and the Beppu City Traditional Bamboo Crafts Center; and traveled to Taketa to meet with the Satoyama Preservation Society to gain a sense of bamboo forestry and conservation.

One of Prof. Carrasco’s long terms goals is to highlight the great beauty of basketry and bamboo art and to find ways of better integrating it into the field of art history in the United States. Recent books and exhibitions have increased awareness of the art form, and Carrasco notes a change in terminology from “baskets” to “bamboo art” – perhaps a linguistic attempt to move bamboo art from the realm of craft to that of fine art and thereby deal with the negative legacy of the decorative-craft/fine art distinction that plagues the discipline of western art history. Carrasco writes, “From an art historical standpoint I am interested in the relationship between these two ways of looking at bamboo art and what transpires as forms move from utilitarian ones or ones for traditional artistic environments, such as the chanoyu, to pieces intended for the gallery or museum, or international art market.”

A second general objective for this project comes from a cultural heritage perspective in which Carrasco is interested in how changing cultural patterns influence material culture and people’s connections to history and tradition. Thus, as Shibata Shozo observes, when basketry and bamboo were superseded by plastic in the 1960s, the results were not simply a change in the material of utilitarian containers, but rather a disruption that affected professions and forestry practices, and ultimately created ecological problems as bamboo groves fell out of management and intruded into arboricultural zones and riparian environments. Due to such changes over time, this rapacious member of the grass family would come to be seen as an invasive problem rather than a bountiful resource, all the while maintaining its place as one of the enduring hallmarks of Japaneseness. In this way, art and craft meet policy and ecology and force us to contemplate how deeply aesthetics are woven into our lives.