Abdullah Brothers

Abdullah Frères, View of Sultan Ahmet Mosque, Constantinople, Turkey. c. 1895. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Abdul Hamid II Collection, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-USZ62-123456]

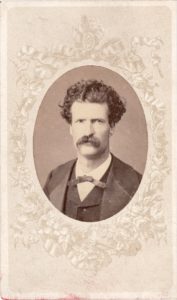

They are best known today for their photos of the Ottoman court, but they also photographed international celebrities, such as Mark Twain, producing carte-de-visites–calling cards that were fashionable at the time. Their ‘realistic’ photographs were not always appreciated by their subjects; the acerbic Twain stated that he might as well send out a photograph of the Sphinx, which, he said, ‘would look as much like him.’[2]

Their most significant Imperial commission was the oversight of the production of a ‘photographic record of the Ottoman State,’ a commission that resulted in an astonishing 51 volumes that contained photographs of landscapes, villages, and the diverse ethnic and religious population of the Empire. Particular emphasis was placed on state-funded schools, and state-sponsored infrastructure. A copy was presented to the Library of Congress by Abdulaziz’s successor– the last Ottoman Sultan, Abdul Hamid II.[3] Intended to document the progress toward ‘modernization,’ these photographs became instead a record of the last days of the Empire.[4]

- Abdullah Frères, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), carte-de-visite; from a sitting on September 1-2, 1867. Schapell Manuscript Foundation, SMC 1683. ©Shapell Manuscript Foundation. All Rights Reserved. For more information, please contact us at www.shapell.org.

- Abdullah Frères, Portrait of Sultan Abdulaziz, 1860s . Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Abdul Hamid II Collection, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-USZ62-123456]