Hürrem Sultan/Roxelana

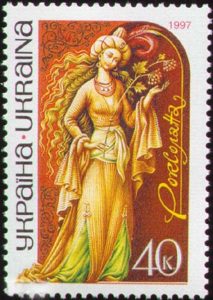

Fig 2. Roxelana, Ukrainian postage stamp, 1997. By Post of Ukraine, Public Domain. Accessed on 8/11/2019.

Fig. 1. Studio of Titian, La Sultana Rossa, 1550s, Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, Collection of the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida.

Roxelana, also known as Hürrem Sultan (c. 1502-1558) began her political career as the favorite (haseki) concubine, and then wife, of Süleyman the Magnificent.[1] She broke with Ottoman traditions and changed imperial norms on the status of women in the court.[2] A woman of firsts, Roxelana was the first wife of a Sultan, the first enslaved court “favorite” to be manumitted, the first wife allowed to bear multiple sons, and the first to act as an advisor to the Sultan.[3]

Roxelana was likely born in modern-day Ukraine. She was taken at a young age by Tartar raiders who eventually brought her to Istanbul. She was purchased by the Süleyman’s mother, the Valide Sultan, as a gift for her son.[4] Known for her joyful temperament (hürrem means “joyful” or “laughing one”) and skill as a singer, she quickly became the Sultan’s favorite.[5] One ambassador claimed that a previous favorite of the Sultan was so jealous of Hürrem that she scratched her face and pulled out her hair to show the Sultan that she was “spoiled meat.”[6] Süleyman, however, was deeply in love with her, calling her his “everything” and even “my sultan” in a love letter.[7] Her son, Selim, became Sultan at Süleyman’s death in 1566, taking the name of Selim II.

Hürrem’s unique position in the imperial court made her an object of fascination beyond the Empire. Both she and her story—or rather, scandalous exaggerations of her story—were depicted in art and written about in pamphlets, plays, and musical works, including a symphony by Haydn.[8] She was most frequently demonized as a sorceress with “boundless ambition.”[9] Her story was used to fuel Western European fears of powerful political women, while also depicting the Ottoman court as a type of “other:” a place where immorality thrived.[10]