Exporting the Exotic: Mummy Brown

- Tube of mummy brown pigment purchased from C. Roberson during the early 1900s. Forbes Pigment Collection, Harvard Art Museums, Straus.17. Photo: R. Leopoldina Torres.

- Martin Drolling (1817), Interior of a Kitchen. Louvre Museum, Paris.

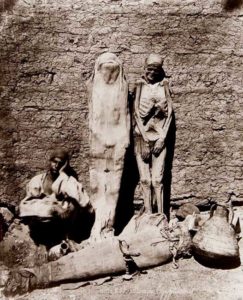

- An Egyptian mummy dealer selling his wares in 1870, Bonfils Family, Momie égyptienne, Medinet-Abou, Egypt, c. 1870, printed later. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum.

Mummy Brown was a pigment of paint that became popular in Europe during the 16th century. The rich brown color was made from grinding up Egyptian mummies, both human and feline.[1] It was prized for its transparency, and was used for painting shadows, glazing, and flesh-tones in both oil and watercolor works of art.[2] In the 19th century, it became a favorite shade of the Pre-Raphaelites, a group of young artists who rejected the “Classical art” (then defined as the style of the Renaissance painter, Raphael) in favor of realism and natural subjects.[3]

While we do not know precisely which paintings from this period were created using Mummy Brown– artists Eugene Delacroix, Sir Willian Beechly, and Edward Burne-Jones are all recorded as having purchased it — it has often been suggested that Martin Drolling’s Interior of a Kitchen uses the pigment.[4]

To make the brown paint, mummies were transported from Egypt, then ground up in Europe to be sold. British chemist and painter Arthur Herbert Church claimed that just one Egyptian mummy could be used to create 20 years’ worth of paint.[5] In addition to paint, mummy powder was also often prescribed by physicians who believed that ingesting the material could cure a variety of illnesses.

The paint fell out of popularity with the Pre-Raphaelites when artists became more aware of its origins. Burne-Jones was reported to have buried his tube of Mummy Brown in his garden when he discovered how it was made.[6] The paint stopped being produced in 1964–largely because there were very few mummies on the market, and they thus were very costly.

[1] R. Leopoldina Torres, “A Pigment from the Depths,” Harvard Art Museums, October 31, 2013, https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/article/a-pigment-from-the-depths.

[2] Philip McCouat, “The Life and Death of Mummy Brown,” Journal of

Art in Society, http://www.artinsociety.com/the-life-and-death-of-mummy-brown.html.

[3] “Pre-Raphaelite,” Tate Museum of Art, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/pre-raphaelite.

[4] Torres, “Pigment from the Depths.”

[5] McCouat, “Life and Death.”

[6] McCouat, “Life and Death.”

Mummy Parties

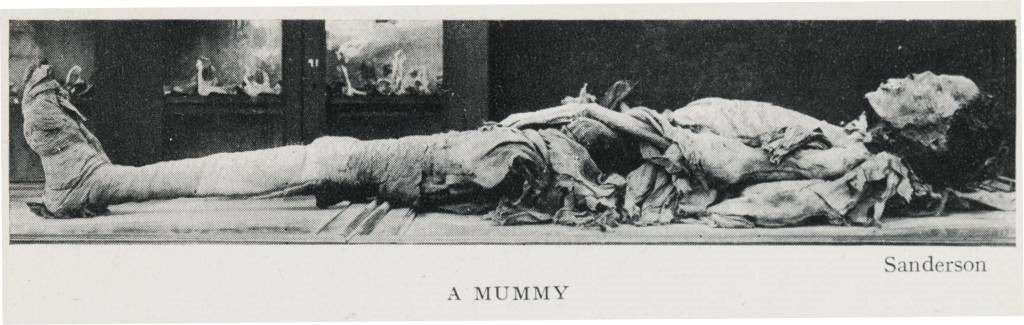

Unknown. A Mummy. 1906. Photograph. Unknown dimensions. Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA), https://hdl.handle.net/1911/20917.

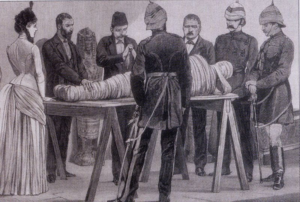

“The work of unrolling the bandages began; the outer envelope, of stout linen, was ripped open with scissors. A faint, delicate odour of balsam, incense, and other aromatic drugs spread through the room like the odour of an apothecary’s shop. The end of the bandage was then sought for, and when found, the mummy was placed upright to allow the operator to move freely around her and to roll up the endless band, turned to the yellow colour of écru linen by the palm wine and other preserving liquids…A vast quantity of linen filled the room, and we could not help wondering how a box which was scarcely larger than an ordinary coffin had managed to hold it all….”[1]

So the French author Theophile Gautier describes the unwrapping of a mummy at the Exhibition of 1857 in Paris. The social event of the year for 19th century elite society, mummy unwrapping parties were all the rage – never mind the potential for incurring the wrath of the mummy!

Parts of mummies had been used since the 16th century as charms, for medicinal purposes, and for making paint. Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt in 1798 took European “Egyptomania” to new heights.[2] According to Abbot Ferdinand de Géramb in a letter dated to 1833, “It would be hardly respectable, on one’s return from Egypt, to present oneself without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other.”[3] The demand for mummy bodies was so great that fakes even began to circulate and flood the tourist market. Mummy parties were hosted all over – from research institutions and public events, to private homes. Attendees would touch and smell the ancient bandages, inspect the body, and admire (and covet) the ancient jewels and “trinkets” found along with the mummy.[4]

Perhaps one of the most famous mummy unwrappings was the January 15, 1834 event hosted by Thomas “Mummy” Pettigrew, a surgeon at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.[5] The event was so popular that even the Archbishop of Canterbury had to be turned away![6]

A bit closer to Tallahassee than Paris or London, in 1852 New Orleans, Louisiana, Egyptologist George Gliddon hosted a mummy party in which the mummies of a 15-year old girl and a priest of the Temple of Amun in Thebes named Djed-Thoth-iu-ef-ankh were unwrapped.[7]

- Philippoteaux, Paul Dominique. Examination of a Mummy – A Priestess of Amun. 1891. Oil on canvas. 183 x 274.5 cm. Private Collection, https://www.bridgemanimages.com/fr/asset/367462/philippoteaux-paul-dominique-fl-1866-87/examination-of-a-mummy-a-priestess-of-amun-c-1891-oil-on-canvas.

- Woodville, Richard Caton II. Unwrapping Ancient Egyptian Mummies in the Boulak Museum at Cairo. 1886. Engraving. Unknown dimensions. Private Collection, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gaston_Maspero_demaillotage.jpeg